Next: Gaussian Process Classifier - Up: Regression Analysis and Classification Previous: Gaussian Process Regression

In both logistic regression and softmax regression considered

previously, we convert the linear regression function

Here in binary GPC, we assume the training samples are labeled

by 1 or -1 (instead of 0) for mathematical convenience, i.e.,

![$\displaystyle p(y=1\vert{\bf x},{\cal D}) = E_f[\sigma(f({\bf x}))]

=\int\sigma(f({\bf x}))\;p(f\vert{\bf x},{\cal D})\,d f$](img1251.svg) |

(265) |

is marginalized (averaged out) in the

integral above, it is hidden instead of explicitly specified,

and is therefore called a latent function.

is marginalized (averaged out) in the

integral above, it is hidden instead of explicitly specified,

and is therefore called a latent function.

For the training set

![${\bf X}=[{\bf x}_1,\cdots,{\bf x}_N]$](img498.svg)

![${\bf f}({\bf X})=[f({\bf x}_1),\cdots,f({\bf x})]^T$](img1252.svg)

is the posterior which can be found

in terms of the likelihood

is the posterior which can be found

in terms of the likelihood

and the prior

and the prior

based on

Bayes' theorem:

As always, the denominator

based on

Bayes' theorem:

As always, the denominator

independent of

independent of

is dropped.

is dropped.

We first find the likelihood

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(268) |

given

given

:

The likelihood of

:

The likelihood of  for all

for all  i.i.d. samples in the

training set

i.i.d. samples in the

training set  is:

is:

|

(270) |

We then consider the prior

|

(271) |

and

and

are more correlated if

are more correlated if

and

and  are close together, but less so if

they are farther apart. However the justification for such a

property is different. In GPR, this property is desired for the

smoothness of the regression function; while here in GPC, this

property is also desired so that function values

are close together, but less so if

they are farther apart. However the justification for such a

property is different. In GPR, this property is desired for the

smoothness of the regression function; while here in GPC, this

property is also desired so that function values

and

and

for two samples

for two samples  and

and  close to each other in the feature space are more correlated and

therefore the two samples are more likely to be classified into

the same class, but less so if they are far apart.

close to each other in the feature space are more correlated and

therefore the two samples are more likely to be classified into

the same class, but less so if they are far apart.

Also, as discussed in GPR, here the parameter

Having found both the likelihood

is not Gaussian, as

the binary labeling

is not Gaussian, as

the binary labeling  of the training set

of the training set  is not

continuous. Consequently, the posterior

is not

continuous. Consequently, the posterior

, as a

product of the Gaussian prior and non-Gaussian likelihood, is not

Gaussian. However, we can carry out Laplace approximation

and still approximate the posterior as a Gaussian:

, as a

product of the Gaussian prior and non-Gaussian likelihood, is not

Gaussian. However, we can carry out Laplace approximation

and still approximate the posterior as a Gaussian:

|

(273) |

and covariance

and covariance

are to be obtained in the following. We further get the log posterior

denoted by

are to be obtained in the following. We further get the log posterior

denoted by

:

The two middle terms are constant independent of

:

The two middle terms are constant independent of  and can therefore be dropped.

and can therefore be dropped.

Now that the posterior

On the other hand, we can also find

|

(280) |

of

of  :

:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(281) |

and

and  . We then

find

and

. We then

find

and

Equatiing the two expressions for

in

Eqs. (275) and (277) we get:

in

Eqs. (275) and (277) we get:

i.e., i.e., |

(285) |

given in Eq. (284) into

the equation and solving it for

given in Eq. (284) into

the equation and solving it for

, we get

, we get

|

(286) |

, in consistence

with the fact that when

, in consistence

with the fact that when

, the log posterior

, the log posterior

, assumed to be Gaussian,

reaches maximum with

, assumed to be Gaussian,

reaches maximum with

. However,

we note that in the equation above,

. However,

we note that in the equation above,

as a value of

as a value of

is expressed in terms of both

is expressed in terms of both  and

and  ,

which in turn are functions of

,

which in turn are functions of  as given in

Eqs. (282) and (283), i.e.,

as given in

Eqs. (282) and (283), i.e.,

given

above is not in a closed form, as

given

above is not in a closed form, as  and parameters

and parameters

and

and  are interdependent. We instead need to

carry out an iteration during which both

are interdependent. We instead need to

carry out an iteration during which both  and the

parameters

and the

parameters  and

and  are updated alternatively:

are updated alternatively:

,

at which

,

at which

is maximized, and

Now that

is maximized, and

Now that  and

and  as well as

as well as

are available, we can further obtain

are available, we can further obtain

in

Eq. (284), and the posterior

in

Eq. (284), and the posterior

.

.

Having found

|

(289) |

in the equation as a Gaussian:

in the equation as a Gaussian:

|

(290) |

and covariance

and covariance

can

be obtained based on the fact that both

can

be obtained based on the fact that both

and

and

are the same Gaussian process, i.e.,

their joint probability

are the same Gaussian process, i.e.,

their joint probability

is a Gaussian. The

method is therefore the same as what is discussed in the method of

GPR. Specifically, we take

the following steps:

is a Gaussian. The

method is therefore the same as what is discussed in the method of

GPR. Specifically, we take

the following steps:

and

covariance

and

covariance

of

of

conditioned

on the latent function

conditioned

on the latent function  , same as in Eq. (258)

for GPR:

, same as in Eq. (258)

for GPR:

as the expectation of

as the expectation of

conditioned on

conditioned on

, i.e. find the average of

, i.e. find the average of

over

over  based on

based on

(marginalize over

(marginalize over  ):

):

given in

Eq. (288).

given in

Eq. (288).

![${\bf\Sigma}_{m_{f_*\vert f}}=E_f[({\bf m}_{f_*\vert f}-{\bf m}_{f_*})^2]$](img1333.svg) .

Given the covariance

.

Given the covariance

of

of  in Eq. (284), we can further find the covariance of

in Eq. (284), we can further find the covariance of

as a linear combination

of

as a linear combination

of  (Recall if

(Recall if

, then

, then

):

):

|

(293) |

of

of  as the sum of

as the sum of

![${\bf\Sigma}_{f_*\vert f}=E[({\bf f}_*-{\bf m}_{f_*\vert f})({\bf f}_*-{\bf m}_{f_*\vert f})^T]$](img1338.svg) for the variation of

for the variation of  with respect to

with respect to

, and

, and

![${\bf\Sigma}_{m_{f_*\vert f}}=E_f[({\bf m}_{f_*\vert f}-{\bf m}_{f_*})^2]$](img1333.svg) for the

variation of

for the

variation of

with respect to

with respect to

:

:

given

in the Appendices.

given

in the Appendices.

Now that the posterior

|

|

|

|

|

![$\displaystyle E_f[ \sigma({\bf f}({\bf X}_*)) ]=\sigma(E_f({\bf f}({\bf X}_*)))

=\sigma( {\bf m}_{f_*} )$](img1348.svg) |

(295) |

.

.

The Matlab code for the essential parts of this algorithm is

listed below. Here X and y are for the training data

Xs is an array composed

of test vectors. First, the essential segment of the main program

listed below takes in the training and test data, generates the

covariance matrices

K, Ks, and Kss, respectively.

The function Kernel is exactly the same as the one used for

Gaussian process regression. This code segment then further calls

a function findPosteriorMean which finds the mean and

covariance of

K=Kernel(X,X); % cov(f,f), covariance of prior p(f|X)

Ks=Kernel(X,Xs); % cov(f_*,f)

Kss=Kernel(Xs,Xs); % cov(f_*,f_*)

[Sigmaf W w]=findPosteriorMean(K,y);

% get mean/covariance of p(f|D), W, w

meanfD=Ks'*w; % mean of p(f_*|X_*,D)

SigmafD=Kss-Ks'*inv(K-inv(W))*Ks; % covariance of p(f_*|X_*,D)

ys=sign(meanfD); % binary classification of test data

p=1./(1+exp(-meanfD)); % p(y_*=1|X_*,D) as logistic function

The function findPosteriorMean listed below uses Newton's method

to find the mean and covariance of the posterior

meanf and covf, respectively, together with w

and W for the gradient and Hessian of the likelihood

function [meanf covf W w]=findPosteriorMean(K,y)

% K: covariance of prior of p(f|X)

% y: labeling of training data X

% w: gradient vector of log p(y|f)

% W: Hessian matrix of log p(y|f)

% meanf: mean of p(f|X,y)

% covf: covariance of p(f|X,y)

n=length(y); % number of training samples

f0=zeros(n,1); % initial value of latent function

f=f0;

er=1;

while er > 10^(-9) % Newton's method to get f that maximizes p(f|X,y)

e=exp(-y.*f);

w=y.*e./(1+e); % update w

W=diag(-e./(1+e).^2); % update W

f=inv(inv(K)-W)*(w-W*f0); % iteration to get f from previous f0

er=norm(f-f0); % difference between two consecutive f's

f0=f; % update f

end

meanf=f; % mean of f

covf=inv(inv(K)-W); % coviance of f

end

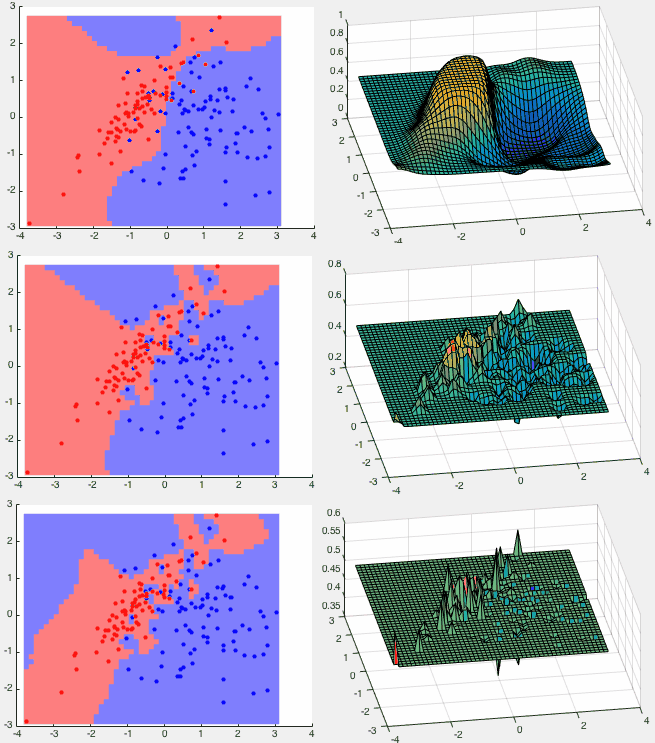

Example 1 The GPC method is trained by the two classes shown in

the figure below, represented by 100 red points and 80 blue points

drawn from two Gaussian distributions

![$\displaystyle {\bf m}_0=\left[\begin{array}{c}1\\ 0\end{array}\right],\;\;\;

{\...

...ht],\;\;\;

{\bf\Sigma}_1=\left[\begin{array}{cc}1&0.9\\ 0.9&1\end{array}\right]$](img1360.svg) |

(296) |

Three classification results are shown in the figure below corresponding

to different values used in the kernel function. On the left, the 2-D

space is partitioned into red and blue regions corresponding to the

two classes based on the sign function of

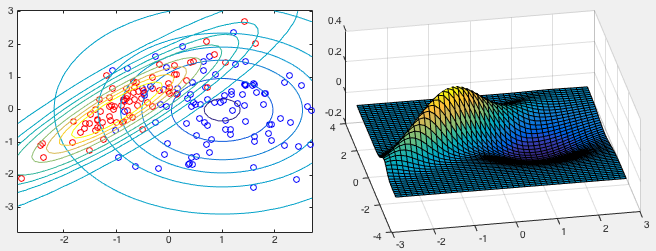

We see that wherever there is evidence represented by the training

samples of either class in red or blue, there are high probabilities

for the neighboring points to belong to either

We make the following observations for three different values of the

parameter

(top row), the space is partitioned into three regions,

with 20 out of 180 training points misclassified. The estimated

distribution is smooth.

(top row), the space is partitioned into three regions,

with 20 out of 180 training points misclassified. The estimated

distribution is smooth.

(middle row), the space is fragmented into several

more pieces for the two classes (blue islands inside the red region

and vice versa), with 5 out of the 180 training points misclassified.

The estimated distribution is jagged.

(middle row), the space is fragmented into several

more pieces for the two classes (blue islands inside the red region

and vice versa), with 5 out of the 180 training points misclassified.

The estimated distribution is jagged.

(bottom row), the space is partitioned into still

more pieces, with all 180 training points correctly classified. The

estimated distribution is spiky.

(bottom row), the space is partitioned into still

more pieces, with all 180 training points correctly classified. The

estimated distribution is spiky.

is small, the classificatioin

result is not necessarily the best as it may well be an overfitting of

the noisy data. We conclude that by adjusting parameter

is small, the classificatioin

result is not necessarily the best as it may well be an overfitting of

the noisy data. We conclude that by adjusting parameter  , we can

make proper tradeoff between error rate and overfitting.

, we can

make proper tradeoff between error rate and overfitting.