The Cahuilla Culture and their Baskets

"...they built up a system that not only supplied their bodily wants, but also gave opportunity to indulge the artistic...side of their being. No one thing so completely combines and exemplifies these facts as their basketry."[3]

THE AREA

The Cahuilla people lived and still do live in Southern California. Their original territory stretched between the San Bernardino Mountain Range and the Chocolate Mountains in the North to Borrego Springs in the South and from Palomar Mountains in the West to the Colorado River to the East. This area included many varied geographical formations such as mountain ranges, canyons, valleys and the desert floor. This area is very harsh in both the summer and the winter. On the desert floor in the summer temperatures can reach 125 F, while winter temperatures can remain below freezing for weeks at a time. Also water sources were highly variable and could change between areas, seasons and from year to year.

Some of the flora in the area were barrel cactus, California fan palm, mesquite, milkweed, Mohave yucca, screw bean, agave, cottonwood, juniper, manzanita and oak just to name a few. Of this they ate acorns, mesquite and screw beans, pinyon nuts, some species of cacti and agave flower buds. Some of the animals in the area that the Cahuilla ate were badgers, chipmunks, cotton tails, mice, deer, raccoons, bighorn sheep, squirrels, quails, ducks, rattlesnakes, ants, grasshoppers and some fish that they caught in mountain streams. However they did not eat the eagle or the raven that were found in the area because of their ritual significance. The Cahuilla also kept dogs to guard their homes from bears or mountain lions. They did this because Mukat, the creator in their creation stories, appointed the dog to guard the home.

CULTURAL CATEGORIZATIONS

There are many groupings within the Cahuilla. The largest is the ?ivi?lyu?atum which is the Cahuilla culture, which is defined by a common language and history. This group was only organized together after European contact.

Another grouping of the Cahuilla was the moiety. The two moieties were Wildcats (tuktum) and coyotes (?istam). Every Cahuilla was part of one of these moieties and was assigned the same moiety as their father. Within a moiety there is mandatory cooperation. Also moieties regulated marriage and ritual. For example, marriage could only be to someone outside the moiety who was not related within five generations. Therefore a moiety did not have geographical boundaries. It was just a categorization of the Cahuilla. However every sib or lineage was all part of the same moiety.

The sib was a group of lineages that acted as a territorial group and political unit. They shared hunting and gathering as well as ceremonies and rituals. There were at least seven sibs within the Cahuilla.

A lineage was often a parent from which others came. Between three and ten lineages made up a sib. Also lineages were the smallest economic unit within the Cahuilla. Therefore in the lineage tasks, possessions and especially food were shared.

SOCIAL STRUCTURE

The 24,000 square mile area that the Cahuilla occupied was divided up into ten or twelve smaller pieces. Each piece was claimed by a sib. Within the sib areas there were multiple villages. Houses in a village were generally situated around a water source. As Bean[4] accounts between 25 to 50 houses could be spread out over a three to five mile area.

The ceremonial house was also centrally located. The lineage leader, or "net" lived in this house. The house had a section that was a sacred sanctuary where the ceremonial bundle, "maiswat", was kept. The ceremonial house also had a dancing area and seating room, a cooking area and a dancing area in front of the house.

Also in the village was a sweathouse. The adult men used this structure for sweating as well as for making community decisions.

Basket making among the Coahuillas belongs to the old women. They sit flat on the ground with the feet thrust out in front. The deft artist holds her work in her lap, at her right lies grass for the foundation, on her left, soaking in a pot of water, her variously colored splints. Her only tool is her awl, wish, anciently of bone or a cactus spine set in a piece of asphaltum; but now a nail serves the purpose, one end pointed, the other in a handle of manzanita wood. The sewing materials are named according to colors-the scraps of juncus, se il; the red portion, i i ul; dyed black are se-il-tu-iksh. Splints from sumac are se-lit and the grass of the foundation suul. No model or pattern is ever used. -Cahuilla[5]BASKETRY

Basketry in the Cahuilla belonged only to the women, but not all women knew how to weave. They wanted to weave, but they did not have the skill for it. The baskets they produced had poor craftsmanship. Unfortunately this skill is fading away with each generation. This was recognized even in the early 1900's. Old basket makers were passing away and no new basket makers were taking their places. In the 20 volume set Indians of North America Edward Sheriff Curits emphasized "The passing of every old man or woman means the passing of a tradition, some knowledge of sacred rites possessed by no other."

The Cahuilla used materials native to the desert they lived in to make their baskets. Cahuilla only made coiled baskets that coiled out in a counterclockwise manner when looking at the bottom of the basket. The basket consisted of filler, the bundle, and the material used to sew the filler to the basket with, the splint. The bundle was usually deer grass while the splint was juncus or sumac. Juncus has a naturally red portion near the root and is overall darker than sumac. Sumac is very light and uniform in color. The Cahuilla boiled juncus with berries to make it black.

Before a basket could be woven the materials had to be gathered and prepared. This process often took a long time. Some materials could only be gathered in certain seasons or certain areas. Therefore it could take months just to prepare materials before any weaving took place. Once the materials were gathered the juncus and the sumac had to be split. Each shoot was split into three pieces. This required the use of both hands and the teeth to guide the splitting. This process was difficult and if it could not be mastered a weaver's career would be very short. Once the material was split it was sized to ensure uniformity. Tin lids from spice jars were used as sizers after European contact. Before European contact holes were made in shells to make sizers.

The actual process of weaving a basket can range from a few hours to a few months. The weaver sat on the ground with her materials. The sewing material was kept in water to ensure that it was pliable. She also had an awl which was the main tool used in the construction of a basket. Bone awls were used before European contact and awls with a carved handle and a nail were used later. The start of a basket was the bottom of a basket and often had a bundle of cactus or palm fiber because they were more pliable. The start is the most difficult part of weaving and is an indication of the level of craftsmanship of the weaver. Once the start is made the bundle is sewn to the last coil by piercing part of the previous coil and putting the juncus or sumac through the hole and around the bundle. A variation of this type of coiling is whole rode coiling. Whole rod coiling uses just one rod or branch as a bundle. Therefore the rod is not pierced with an awl. Instead the juncus or sumac is sewn completely around the previous coil.

When the end of each piece splint is reached the end is either cut off in the inside of the basket if the weave is tight enough or it is drawn back through the previous "stitch" to make a "fag" end. Another characteristic of Cahuilla basketry is that the last coil around the top of the basket is almost always completely a light color.

For the Cahuilla there were three basic basket forms. The flat round basket that looked like a tray was called "chi-pat-mal." These trays were used to hold food and to gamble with. The second form was the round basket called the "ka-put-mal." It held grain, fruit and seeds. This name was also the name for burden baskets. The third form for the Cahuilla was the "te-vig-nil." This basket was more spherical then the last form. This was the form most gift baskets took.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries basketry became more a work of art and done less for utility purposes. Instead of baskets the Cahuilla were using modern utensils, plates, pots, etc. Also, since it is more a work of art the designs became more elaborate.

There are three classes of designs in Cahuilla culture. The first class contains designs with obvious meanings to any observer. This includes snakes, people, animals, mountains, stars, lightning, etc. The second class of designs was patterns or objects that have certain meaning to the maker and the tribe. For example the swastika is seen on many Cahuilla baskets. It is the symbol for good luck and it symbolizes the circle of life: birth, growth, parent and death. Other symbols for good luck were the eagle, double arrow point, figure 8 and peace pipe. The eagle was also the symbol for superiority. The third class of designs had no interpretation. They were simply patterns with no meaning that looked attractive to the weaver or perhaps the buyer. The most often reason for changing from the old designs was to attract a white buyer during the craze for Native American basketry during the late 1800's and early 1900's. The best way to know that a design has not interpretation is that more and more older women cannot interpret the design.

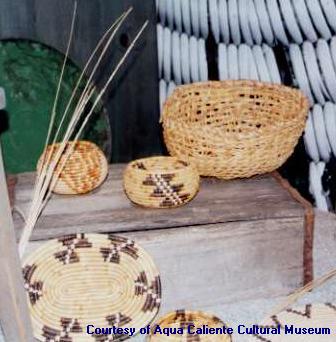

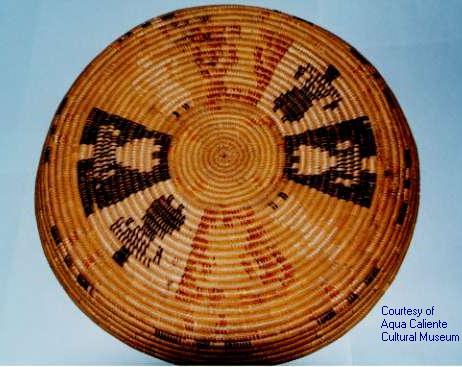

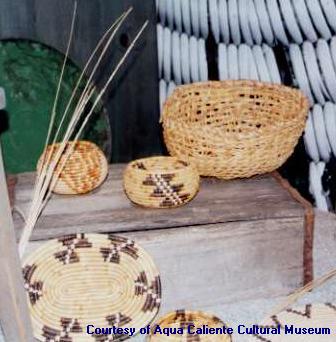

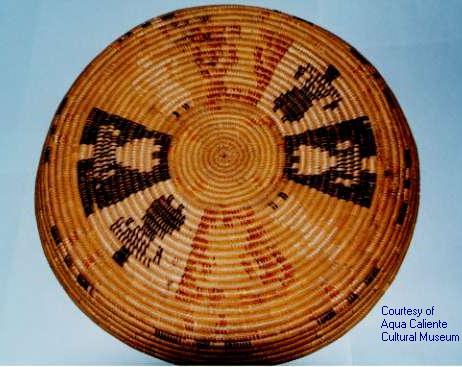

PICTURES OF CAHUILLA BASKETS

A beautifully crafted Cahuilla basket

A Cahuilla tray

Some more cahuilla basketry

The start of a coiled basket with the tools used to make a coiled basket surrounding it: an awl, a knife and a tin lid sizer. Also, the basket on the left has a lightning design on it.

Awls, including a bone awl, and tin lid sizers.

Splints: Juncus on the right, sumac on the left.

A basket with two sets of negative images. The black was dyed with rotting acorns, rusting iron or berries. The red is the bottom portion of a juncus plant. The lightest color is sumac and the rest is made of the majority of the juncus shoot.

European design of rabbits. The coils just previous to the rabbit look as though a rattlesnake pattern was intended. Possibly a buyer requested rabbits, and the design was changes to make a sale.

European addition to the form of the basket. The pedestal is a nontraditional addition because the pedestal serves no useful function. It may have been simply copied from European designs of requested by a buyer.

Background image courtesy of Agua Caliente Cultural Museum.